Chapter 13: Integration between disaster risk reduction and national climate adaptation strategies and plans

13.1 Disaster and development risks from climate change

13.1.1 Risk from climate change is profound and urgent responses are needed

Current national commitments to reduce GHG emissions and otherwise mitigate global warming under the Paris Agreement will not contain global warming within 2°C above pre-industrial levels, let alone the preferred containment within 1.5°C. The 2018 IPCC special report Global Warming of 1.5°C (IPCC SR1.5) projects that, based on Member States' current NDCs, the climate system is heading off track into the territory of 2.9°C to 3.4°C warming. If this happens, it would take future hydrometeorological hazard extremes well outside the known range of current experience and alter the loss and damage equations and fragility curves of almost all known human and natural systems, placing them at unknown levels of risk. This would render current strategies for CCA and DRR, in most countries, virtually obsolete. It also means that it is no longer sufficient to address adaptation in isolation from development planning, and that sustainable socioeconomic development, by definition, must include mitigation of global warming.

IPCC SR1.5 and its Fifth Assessment Report (published in 2014 ) have also reiterated that global warming triggers climate change effects that are not linear. This is based on multiple lines of evidence, including on observations already made in recent decades and on the projections of a range of different global climate models about future effects. So even if global warming is contained within the range of 1.5°C to 2°C, there will be very significant health and socioeconomic effects due to increasing average temperatures. In addition, and significantly for understanding and reducing risk, humanity now faces the current reality and the future prospect of more-extreme and much-higher-frequency "natural" hazards - extremes of cold to heat-waves, longer and more sustained droughts, more-intense and more-frequent storm events, heavier rainfall and more flooding. This means that the line between DRR and CCA, if indeed such a line ever existed, is no longer possible to discern. Climate change is by no means the only source of disaster risk. As the foregoing parts of this GAR have emphasized, sources arise from a range of other geological, environmental, biological and technological hazards and the system risks these generate. Climate change is increasing the risk of disaster - from single climatological events, and also from sustained global warming, thus cascading risk from impacts on human systems in the short, medium and long terms.

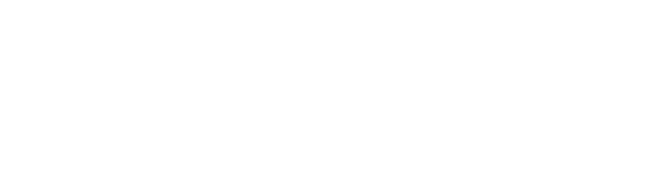

In this sense, CCA can be characterized as essentially a subset of DRR. Climate mitigation can also be understood as a subset of development planning. The main policy implication if this analysis, within the risk framework of this GAR, is that at a minimum, CCA needs to be integrated with DRR, and that governments need to move to a coherent policy approach that sees both of these risk reduction measures as integral to planning for sustainable development.

This situation has become much clearer since the Sendai Framework was agreed in 2015. There is also no obligation on Member States to divide their policy formulation and implementation according to the scope of different international agreements negotiated along thematic lines. Accordingly, this chapter is an account of a range of country policy practices on integration of CCA and DRR. It also gives some examples of fuller integration into development planning and an exhortation to governments to explore more fully the efficiency and effectiveness benefits of taking a systems approach to disaster and climate risk.

13.1.2 International framework

As part of the processes and mechanisms under the 1992 UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement established a global goal on adaptation of enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change, with a view to contributing to sustainable development and ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of the temperature goal referred to in Article 2: "Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change."

For many years before the Paris Agreement, during the climate negotiations and since 2015, there has been considerable debate about the likely differences in impact between warming of 1.5°C and 2°C, focusing on the capacity and scope for adaptation. Since 1990, this debate has included a strong message from the Alliance of Small Island States that containment of warming within 1.5°C was essential for socioeconomic survival of its members, and in many cases their physical existence, due to projected sea-level rise and other climate change impacts.

As the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, IPCC was created in 1988, to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on climate change, its implications and potential future risks, as well as to put forward adaptation and mitigation options. Its assessment reports, based on the work of a large network of experts globally, have long been familiar to policymakers in the fields of environmental protection and hydrometeorology. Its work is also now widely recognized as relevant to policymakers concerned with the broader agendas of development planning and DRR.

The last major synthesis report of the IPCC, the Fifth Assessment Report, was published in 2014, and was based on research undertaken around the 2012 Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. These remain current and relevant resources. However, the 2018 IPCC SR1.5 is a special report that addresses the probable differences in impacts of global warming of 1.5°C compared with 2°C, specifically "in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty." It is a compelling new resource that makes it clear that addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation is an urgent global and national priority for DRR strategies as part of planning for risk-informed socioeconomic development, in particular that containing global warming within 1.5°C will reduce the impacts significantly compared with 2°C warming. Relevant highlights of IPCC SR1.5 are considered here as an essential context for addressing questions of disaster and climate risk at national policy level.

13.1.3 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report 2018 - Global Warming of 1.5°C

The IPCC SR1.5 highlights that the global climate has already changed relative to the pre-industrial period and that these changes have affected organisms and ecosystems, as well as human systems and well-being. Human activities have already caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, which this has led to multiple observed changes including more extreme weather, frequent heat-waves in most land regions, increased frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events, increased risk of drought in the Mediterranean region, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice. If global warming continues at the current rate of 0.2°C per decade, the surface of the planet will warm by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052, causing further changes.

Future climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth depend on the rate, peak and duration of warming, but risks to natural and human systems are expected to be lower at 1.5°C than at 2°C of global warming. Future risks at 1.5°C of global warming will depend on the mitigation pathway and on the possible occurrence of a "transient overshoot" (i.e. if the increase goes above 1.5°C but later returns to the 1.5°C level). The impacts on natural and human systems would be greater if mitigation pathways cause such a temporary overshoot above 1.5°C warming and then return to 1.5°C later in the century, as compared with pathways that stabilize at 1.5°C without an overshoot. That is, it is far preferable to ensure that the increase does not ever exceed 1.5°C warming. This would avoid climate change impacts on sustainable development, and support efforts to eradicate poverty and reduce inequalities, if mitigation and adaptation synergies are maximized while trade-offs are minimized.

Some aspects of climate risk most relevant to adaptation strategies at national level - and which also highlight the urgency of integrating climate change mitigation into all development strategies to avoid these risks eventuating in their more extreme forms - are highlighted below:

Extreme hazard events

- Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would limit risks of increases in heavy precipitation events on a global scale and in several regions, and reduce risks associated with water availability and extreme droughts.

- Human exposure to increased flooding is projected to be substantially lower at 1.5°C than at 2°C of global warming, although projected changes create regionally differentiated risks.

Human health

- Every extra bit of warming matters for human health, especially because warming of 1.5°C or higher increases the risk associated with long-lasting or irreversible changes.

- Lower risks are projected at 1.5°C than at 2°C for heat-related morbidity and mortality, and for ozone-related mortality if emissions that lead to ozone formation remain high.

- Urban heat islands often amplify the impacts of heat-waves in cities.

- Risks for some vector-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever, are projected to increase with warming from 1.5°C to 2°C, including potential shifts in their geographic range.

Impacts on ecosystems and species important for human food and livelihoods

- Constraining global warming to 1.5°C, rather than to 2°C and higher, is projected to have many benefits for terrestrial and wetland ecosystems and for the preservation of their services to humans.

- Risks for natural and managed ecosystems are higher on drylands than on humid lands.

- If global warming can be limited to 1.5°C, the impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems and on terrestrial, freshwater and coastal ecosystems are projected to be lower than at 2°C of global warming.

- Limiting global warming to 1.5°C is projected to reduce risks to marine biodiversity, fisheries and ecosystems, and their functions and services to humans, as illustrated by recent changes to Arctic sea ice and warm-water coral reef ecosystems.

- Risks of local species losses and, consequently, risks of extinction are much less in a 1.5°C versus a 2°C warmer world.

Agriculture and fisheries

- Limiting global warming to 1.5°C, compared with 2°C, is projected to result in smaller net reductions in yields of maize, rice, wheat and potentially other cereal crops, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, and Central and South America.

- Reductions in projected food availability are larger at 2°C than at 1.5°C of global warming in the Sahel, Southern Africa, the Mediterranean, Central Europe and the Amazon.

- Fisheries and aquaculture are important to global food security but are already facing increasing risks from ocean warming and acidification. These risks are projected to increase at 1.5°C of global warming and affect key organisms such as fin fish and oysters, especially at low latitudes.

- Small-scale fisheries in tropical regions, which are very dependent on habitat provided by coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass and kelp forests, are expected to face growing risks at 1.5°C of warming because of loss of habitat.

Regional differences in impacts

- Climate models anticipate robust regional climate differences within global warming. For instance, temperature increases in sub-Saharan Africa are projected to be higher than the global mean temperature increase.

- The differences in the risks among regions are also strongly influenced by local socioeconomic conditions. Depending on future socioeconomic conditions, limiting global warming to 1.5°C, compared to 2°C, may reduce the proportion of the world's population exposed to a climate-change-induced increase in water stress by up to 50%, although there is considerable variability among regions. Regions with particularly large benefits could include the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. However, socioeconomic drivers are expected to have a greater influence on these risks than the changes in climate.

Small islands

- Small islands are projected to experience multiple interrelated risks at 1.5°C of global warming, which will increase with warming of 2°C and higher levels. Climate hazards at 1.5°C are projected to be lower than those at 2°C.

- Long-term risks of coastal flooding and impacts on populations, infrastructures and assets, freshwater stress, and risks across marine ecosystems and critical sectors are projected to increase at 1.5°C compared with present-day levels and increase further at 2°C, limiting adaptation opportunities and increasing loss and damage.

- Impacts associated with sea-level rise and changes to the salinity of coastal groundwater, increased flooding and damage to infrastructure are projected to be critically important in vulnerable environments, such as small islands, low-lying coasts and deltas, at global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C.

- Projections of increased frequency of the most intense storms at 1.5°C and higher warming levels are a significant cause for concern, making adaptation a matter of survival. In the Caribbean islands for instance, extreme weather linked to tropical storms and hurricanes represent one of the largest risks facing nations. Non-economic damages include detrimental health impacts, forced displacement and destruction of cultural heritages.

Economic growth

- Risks to global aggregated economic growth due to climate change impacts are projected to be lower at 1.5°C than at 2°C by the end of this century.

- The largest reductions in economic growth at 2°C compared to 1.5°C of warming are projected for low- and middle-income countries and regions (the African continent, South-East Asia, Brazil, India and Mexico).

- Countries in the tropics and southern hemisphere subtropics are projected to experience the largest impacts on economic growth due to climate change should global warming increase from 1.5°C to 2°C.

(Source: IPCC SR1.5 2018, summary based on inputs from Wilfran Moufouma-Okia, IPCC)

13.2 Synergies between climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction

CCA and DRR efforts share the immediate common aim of building resilience of people, economies and natural resources to the impacts of extreme weather and climate change. But IPCC SR1.5 makes it clearer than ever that climate change may lead to changes in risk levels for non-climate hazards, including impacts on food security and human health due to cascading risks from higher temperatures, warmer seas, sea-level rise and others. As already described in the foregoing chapters of this GAR, the Sendai Framework requires policymakers to contemplate disaster risk from a multi-hazard perspective that includes the traditionally recognized natural hazards that lead to disasters, as well as a range of human-made and mixed hazards, especially the newly included environmental, technological and biological hazards and risks, described in Part I of this GAR.

While DRR has a much wider scope than climatological hazards, CCA is also much more related to more extreme hydrometeorological hazards and warmer temperatures than DRR. Chapter 2 of this GAR provided significant insights into how multiple risks cascade, and how complex systems respond to shocks in ways that are not linear, making the impacts difficult to predict through traditional hazard-by-hazard monitoring, so that a systems approach is needed for effective risk management.

From a policy and governance perspective, climate and disaster risks present a significant degree of uncertainty in estimating potential impacts. This is due to the complex nature of the phenomena, as well as limitations in science and technology to understand projected events and how exposed people and assets will react, due to varied sources and types of vulnerability. However, understanding the commonalities and differences between DRR and CCA in each national context is important for policy coordination, especially if a decision is made to integrate DRR and CCA into one national or local strategy. In some cases, the two are also mainstreamed into risk-informed socioeconomic development planning; it is then essential not to lose sight of the full range of risks that need to be considered, and to include the short-, medium- and long-term timescales required for a systems approach.

Figure 13.1. A systems approach to risk reduction: the Sendai Framework, 2030 Agenda and Paris Agreement recognize the need for policy integration on disaster, development and climate risk

The question of policy coordination, integration and synergies between CCA and DRR has national and international dimensions. At the national level, governments tend to mandate different departments to deal with the two issues separately, with some few exceptions discussed in the following sections on country experiences. DRR is usually aligned with national disaster management agencies, civil protection and response. Given its evolution as an environmental issue, climate change tends to be coordinated through ministries of the environment, in close coordination with finance and planning ministries. Having two departments lead the two agendas separately ensures high cabinet representation, especially in larger countries with more ministries. The downside is that, in some cases, there is little coordination between these activities. The source of financing is also a major factor in the degree of integration of the two issues, with different streams of international financing sometimes encouraging silos at national level simply due to the funding criteria and compliance requirements.

At the international level, Member States have agreed to different elements in terms of reporting, funding and other mechanisms for their implementation under the Paris Agreement and the Sendai Framework. As with the national level, the two agendas being governed by separate agreements and mechanisms ensure effective international representation. Decisions are in place to promote synergy and coherence in the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the Sendai Framework, while the 2030 Agenda provides the common basis for coordinating the implementation of the two, as disasters and climate change have the potential to severely affect development efforts. As discussed in Part II of this GAR, practical coordination for international reporting is in the early stages, and Member States need to address very distinct reporting requirements and funding streams for CCA and DRR. However, there are also new initiatives to integrate CCA, climate change mitigation, DRR and sustainable development agendas.

In considering integrated approaches, Member States can also try to avoid some of the perhaps-artificial divisions that occur in international agreements due to the negotiation process and established organizational mandates. For example, one analysis is that the mentions of climate change in the Sendai Framework put too much emphasis on the hazard part of disaster risk, rather than providing further support for an all-vulnerabilities and all-resilience approach that includes climate change and development. It may also be helpful in organizing institutional responsibilities at national level to think of CCA as a subset within DRR and climate change mitigation as a subset within sustainable development, even if the choice has been made to establish a separate legal or institutional framework to deal with climate change holistically, based on gathering together national experts in the whole field, or to more easily meet international reporting requirements.

Positive evidence of synergy is already seen in Member States' reports on NDCs under the Paris Agreement. More than 50 countries referenced DRR or DRM as part of their NDC. Colombia and India made explicit references to the Sendai Framework in their NDCs

13.3 Guidance and mechanisms for integrated climate change adaptation under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

13.3.1 Evolution of technical guidance on national adaptation plans

At the global level, specific goals and guidance for Member States to conduct CCA comes from UNFCCC, especially the Paris Agreement, as does an increasingly important stream of public international financing for CCA through the UNFCCC financial mechanism, especially the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

UNFCCC has a process to formulate and implement NAPs, which was established in 2010 under the UNFCCC Cancun Adaptation Framework. These types of plans began in 2001 as an initiative only for the least developed countries to formulate NAPAs and thereby access the Least Developed Countries Fund. However, since 2010, there has been a shift to NAPs as a relevant tool for all developed and developing countries. UNFCCC developed initial guidelines for the formulation of NAPs in 2011, which outline four main elements and instruct countries to lay the groundwork and address gaps, develop preparatory elements, establish implementation strategies, and report, monitor and review them on a regular basis.

In 2012, the UNFCCC Least Developed Countries Expert Group developed technical guidelines for the process to formulate and implement NAPs. These are: (a) to reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, by building adaptive capacity and resilience, and (b) to facilitate the integration of CCA in a coherent manner, into relevant new and existing policies, programmes and activities, in particular development planning processes and strategies, within all relevant sectors and at different levels, as appropriate.

DRR is not explicitly mentioned in the initial guidelines for NAPs/NAPAs, and they principally address climate-related hazards, typically droughts, floods, sea-level rise and severe storms. However, recent and ongoing efforts by countries to develop NAPs and to undertake broad national and local adaptation planning according to their own needs assessments, provides a clear opportunity for countries to consider multiple risks in development decisions and accelerate the common goal of climate and disaster-resilient development.

Focusing on this opportunity, a supplement to NAP technical guidelines to countries was developed from a disaster risk angle in 2017 specifically dedicated to "promoting synergy with DRR in National Adaptation Plans". In 2018, the UNFCCC Adaptation Committee considered a report from an expert meeting focused on national adaptation goals/indicators and their relationship with SDGs and the Sendai Framework.

The supplementary guidance aims to provide national authorities in charge of adaptation planning, as well as the many actors involved in adaptation, with practical advice on when and how to incorporate DRR aspects in the adaptation planning process. It also aims to give DRM authorities a better understanding of the NAP process, including advice on how they can contribute to and support its development, and to prompt central planning authorities such as ministries of planning and finance on how to use national adaptation planning in shaping resilient development.

13.3.2 Taking the next step - fully integrated development planning

Considering the commonalities in the approaches and requirements of integrating DRR and sustainable resilient development in national CCA strategies such as NAP and NAPA processes, three major actions seem to be most conducive to success. Firstly, establishing a strong governance mechanism that involves all relevant stakeholders across disciplines, which helps avoid ineffective and inefficient action, communication and cooperation. Secondly, developing a central and accessible knowledge management platform and risk assessment system for CCA and DRR with a balanced combination of scientific and local knowledge, good practices, natural and social scientific data, and risk information. And lastly, redesigning funding schemes and mechanisms to support coherent CCA and DRR solutions encourages cooperation and coordination for efficient use of financial resources. The technical expert meeting on adaptation in Bonn, Germany, in 2017 made recommendations to countries to bring DRR and CCA together to ensure sustainable development.

Key recommendations:

- While maintaining the autonomy of each of the post-2015 frameworks, improved coherence of action to implement the three frameworks can save money and time, enhance efficiency and further enable adaptation action.

- Both "resilience" and "ecosystems" can act as core concepts for motivating integration. Actors, including State and non-State, operating across multiple sectors and scales ranging from local to global, can facilitate policy coherence, and vulnerable people and communities can benefit from and initiate effective bottom-up, locally driven solutions that contribute to multiple policy outcomes simultaneously.

- Building the capacity for coherence and coordination will help to clarify roles and responsibilities and to encourage partnerships among a wide range of actors.

- The availability of data, including climate and socioeconomic data, and their resolution remain a challenge, especially in Africa. Better data management, more informed policymaking and capacity-building are needed.

- The process to formulate and implement NAPs can effectively support the implementation of enhanced adaptation action and the development of integrated approaches to adaptation, sustainable development and DRR, thanks in part to its demonstrated success as a planning instrument, the resources available for its support, its iterative nature and flexible, nationally driven format.

- Adequate, sustainable support for adaptation efforts from public, private, international and national sources is crucial. Accessing finance and technology development and transfer and capacity-building support is also critical, particularly for developing countries.

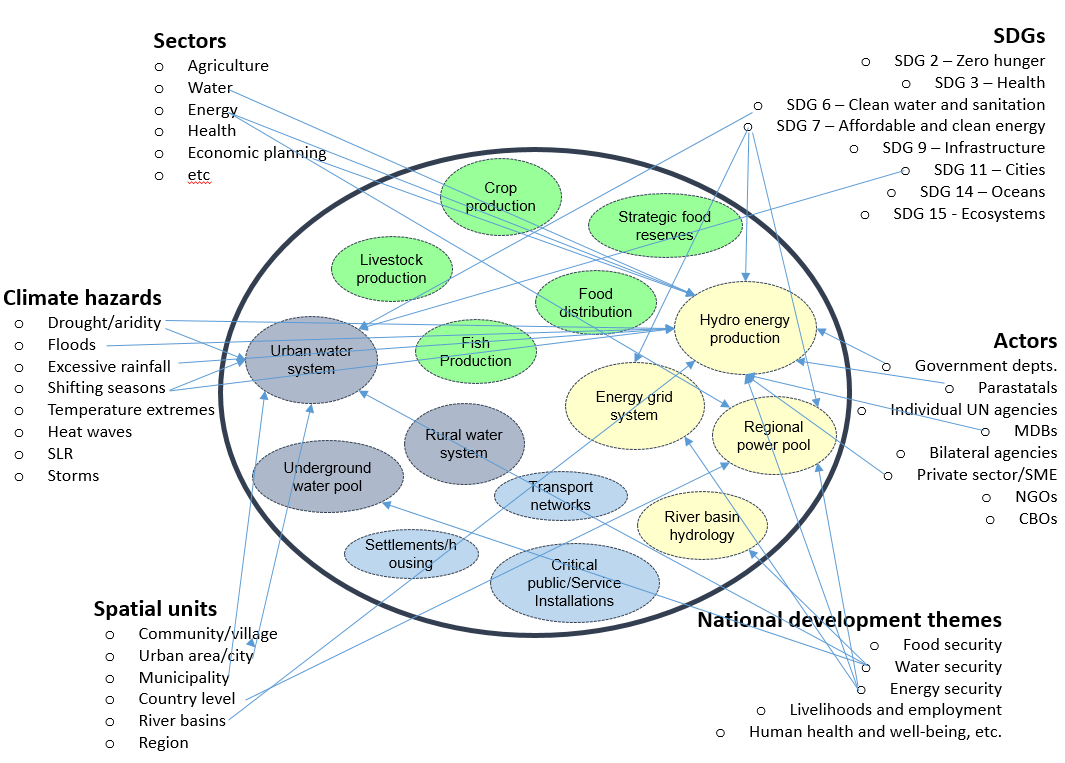

13.3.3 National Adaptation Plan Sustainable Development Goals Integrative Framework

To support the formulation of NAPs that integrate well with development planning, the UNFCCC Least Developed Countries Expert Group developed the NAP-SDG Integrative Framework (iFrame) that facilitates integration of different entry points to planning by managing relationships between the entry points and the systems being managed. By focusing on the systems that are key to a country's development, it is possible to map to different drivers (climatic hazards for instance), as well as to sectors or ministries, specific SDGs, different spatial units, development themes or other frameworks such as the Sendai Framework. See Figure 13.2, which shows a sample collection of systems in the middle. These systems become the focus of assessment and subsequent planning and actions to address adaptation goals. The achievement of particular SDGs is ensured by ensuring that all the necessary systems of governance relevant to that goal are included in the analysis and subsequent action.

NAP-SDG iFrame is being tested in some countries. Early results indicate that this systems approach is very effective at focusing on outputs and outcomes that would have the greatest impact on development dividends, while avoiding the bias inherent when actors that would promote their interests over those of more essential systems, and also helps ensure multiple frameworks are simultaneously addressed. The approach has the potential to manage multiple and overlapping climatic factors or hazards, and should facilitate governance and synergy among different actors and ministries. The systems can be singular, as in the case of nexus approaches, or compound, to represent development themes such as food security, which would invariably include aspects of crop/food production, as well as other aspects of food availability, access and utilization. This approach lends itself to easy design and implementation of integrated models for the system to facilitate assessment of climate impacts and potential losses within a broader development framework. It also becomes easy to assess impacts of one or multiple interacting climatic drivers or hazards, as it is often the case that countries may be faced with multiple hazards in a given year such as serious drought, flooding, shifting seasons and heat-waves, resulting in multiple exposure.

The systems at the centre of the iFrame can be defined in a manner that makes sense for the country, and can include value or supply chains, each with an implied scale and models of drivers and interacting parts, and with specific pathways for how climatic or other natural hazards would have an impact. iFrame can be applied to dissolve working in silos and to manage different lenses to adaptation, and should open up completely new horizons and developments in adaptation planning, implementation, monitoring and assessment, and knowledge management.

Figure 13.2. Collection of sample national systems showing links to multiple entry point elements including SDGs, as part of NAP-SDG iFrame, being developed by the UNFCCC Least Developed Countries Expert Group

13.4 Selected country experiences with integrated climate and disaster risk reduction

13.4.1 Enabling legislation and institutions

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), in collaboration with United Nations organizations and donors, has developed tools to support countries to strengthen their legal and policy frameworks for DRR and CCA. The Checklist on Law and Disaster Risk Reduction is a succinct and easy-to-use assessment tool that, by guiding a research and assessment process, helps countries identify strengths in legal frameworks. These are areas where greater focus is needed on implementation, as well as whether drafting or revision of legislation is necessary. Another relevant tool is the Law and Climate Change Toolkit. This is a global electronic resource designed for use by national governments, international organizations and experts engaged in assisting countries to implement national climate change laws.

To establish a strong governance mechanism, strategies benefit from an enabling legal framework, which also applies to integrated DRR and CCA strategies. Recent reviews of DRR laws and regulations in various countries indicate that the integration of DRR and CCA into legal frameworks remains the exception rather than the rule. The trend in the countries reviewed has been to allocate responsibility for the administration of CCA laws to ministries of environment, without requiring them to coordinate with DRM institutions, while DRM institutions are also not required to coordinate with Ministries of Environment. Only more recently have some countries, especially in the Pacific but including countries in other regions also, are adopting a new model in which CCA and DRR are integrated with development planning and resource management legislation.

Some examples of such integrated legal frameworks outside the Pacific include Algeria, Mexico and Uruguay. In Algeria, the National Agency on Climate Change, based in the Ministry for the Environment, is responsible for mainstreaming CCA into development planning. However, as Algeria's National Committee on Major Risks, established by law, is mandated to coordinate all activities on major risks, including implementation mechanisms for CCA and DRM institutions, it provides an overarching coordination mechanism. The enabling law for this in Algeria is the 2004 Law on Prevention of Major Risks and Disaster Management. This legal and institutional framework has the potential to achieve a high level of CCA and DRR integration if implemented as planned.

In Mexico, the General Climate Change Law of 2012 is supported by a special national climate change programme and an Inter-Ministerial Commission on Climate Change, which is a cross-sectoral coordination body formed by the heads of 14 federal ministries. In Uruguay, a special decree, the National Response to Climate Change and Variability, was passed in 2009. Implemented by the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment, its purpose is to coordinate actions among all institutions relevant to achieving risk prevention in the whole territory.

13.4.2 Financing

Financing for adaptation and DRR is a key element for enhancing capacity and ensuring successful implementation. Although many countries have undertaken climate and disaster risk assessments, the systematic integration of these assessments into national financial and fiscal planning processes is still limited. This suggests a need to redesign funding schemes and mechanisms to encourage cooperation and coordination for efficient use of financial resources.

International public financing of CCA is now also a major resource and influence on national approaches. GCF was set up in 2010 by Parties to UNFCCC as part of the Convention's financial mechanism to increase financial flows from developed countries to developing countries for mitigation and adaptation. It implements the financing provisions of the Paris Agreement (especially Article 9) aimed at keeping climate change well below 2°C by promoting low-emission and climate-resilient development, at the same time taking into account the needs of countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts. It is the most significant source of public international financing for national adaptation planning (through a range of instruments such as grants, concessional debt financing, equity and guarantees), with $5 billion already committed by early 2019 and over 100 country mitigation and/or adaptation projects under way through accredited partners.

Many of the GCF adaptation projects integrate components that would often be seen as DRR or sustainable development. This indicates the extent of policy coherence or integrated risk governance that is already being made possible under this mechanism. Projects are explicitly documented in relation to the SDGs that they help to implement. The criteria include safeguards for indigenous peoples, gender mainstreaming and environmental and social safeguards. For example, a project just commenced in Namibia is on building resilience of communities living in landscapes threatened under climate change through an ecosystems-based adaptation approach (Project SAP006). It gives GCF results areas (health, food and water security; livelihoods of people and communities; and ecosystems and ecosystem services) as well as the SDGs that it supports (SDG 13 on climate action; SDG 14 on life below water; and SDG 15 on life on land). In DRR terminology, this project is also about drought resilience. It is hoped that this clear move towards integrated risk governance by GCF will encourage integrated project proposals from countries where disaster and climate risk have significant overlaps, either generally or in specific regions or sectors.

13.4.3 Risk information

An integrated CCA/DRR policy, strategy or plan needs to be complemented by adequate, accessible and understandable risk information. Ideally, this is an available resource during the policy development stage, to help formulate objectives and goals, but joint risk assessments and ongoing information sharing are key elements of integrated strategies.

A study in Vanuatu identified a well-developed DRR operational governance structure comprising many government levels and non-governmental actors working together to implement top-down and bottom-up DRR strategies that contemplate CCA elements. Stakeholders in Vanuatu accept local and scientific risk knowledge to inform DRR policies, although scientific knowledge is still precedent for the development of formal instruments to reduce disaster risk.

Several good practices in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have been identified. These include strong support for the assessment of flood and climate risk through the Adaptation Reporting Powers under the Climate Change Act, which encouraged key infrastructure institutions to consider the impacts of hazards such as flood and climate change on their business and the provision of key services. Additionally, the government encourages use of ecosystem-based approaches (e.g. sustainable urban drainage) and infrastructure that has the flexibility to be adapted in the future (e.g. the flood defence walls implemented in Morpeth, north-east England, which have been constructed so that they can be modified easily if required in the future ).

A Regional Initiative for the Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources and Socio-Economic Vulnerability in the Arab Region (RICCAR) assesses the impacts of climate change on freshwater resources in the Arab region and their implications for socioeconomic and environmental vulnerability. It does so through the application of scientific methods and consultative processes involving communities in CCA and DRR. The initiative prepares an integrated assessment that links climate change impact assessment outputs to inform an integrated vulnerability assessment to climate change impacts, such as changes in temperature, precipitation and run-off, droughts or flooding due to shifting rainfall patterns and extreme weather events. The RICCAR example shows that joint assessments and knowledge development involving two otherwise siloed communities of experts can help build a common understanding of risk, which is the precondition for planning and budgeting.

13.4.4 National adaptation plans

Although NAPs are developed by many countries, the focus for UNFCCC monitoring is on developing countries, and it maintains a public database of these, NAP Central. As at 30 January 2019, 12 NAPs from developing country Parties were developed and submitted on NAP Central between 2015 and 2018, namely Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, Colombia, Fiji, Kenya, Saint Lucia, Sri Lanka, State of Palestine, Sudan and Togo. All of these include aspects of DRR, providing scope for increased coherence between

DRR and broader adaptation during the implementation of NAPs.

When evaluating the latest developing country examples of NAPs, which seem to have great potential for integration with DRR, a survey was conducted that showcases the following case studies of country experiences.

13.4.5 Other integrated strategies and plans

Well-defined national legislation can set the preconditions for successful integration of DRR and CCA, and establish a coordination mechanism, but defining and coordinating institutional arrangements for climate- and disaster-resilient development often remains difficult. This can be due to institutional resistance, given that different institutions have historically driven climate change and DRM agendas with separate financial sources. Emerging experience indicates that to have effective convening power, the relevant agency should be located at the highest possible level of government. Indeed, as climate and disaster risk affect multiple sectors, the lead agency needs to have a strong convening power of decision makers from multiple agencies and levels of government, as well as the private sector and civil society.

13.5 Pacific region approach to integrated climate, disaster and development policy

13.5.1 Regional approach to support integration - Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific

As noted in section 10.1 on regional approaches and in section 11.5 on integration, the Pacific region is leading the way, at regional and country levels, in integrating reduction of climate and disaster risk with development planning in FRDP.

Although it is not prescriptive, FRDP suggests priority actions to be used as appropriate by different multi-stakeholder groups, at regional and national levels, in sectors or other groupings as appropriate. Its implementation was also supported by the Pacific Resilience Partnership established by Pacific leaders in 2017 for an initial trial period of two years. The partnership works to strengthen coordination and collaboration, working with a multi-stakeholder task force, a support unit, technical working groups and Pacific resilience meetings.

13.5.2 Pacific countries

Given the importance of climate-related disasters in the Pacific Islands, many countries of the region have developed JNAPs, action plans that consider DRM and CCA, since 2010. This process began well before the 2016 FRDP, which is a regional evolution from national practice.

JNAPs normally reflect a recognition of the relationship among development, disaster and climate risk and the role of environmental management in development and risk management. The Cook Islands, the Marshall Islands, Niue and Tonga represent some of the countries that have developed and published their JNAPs, while Vanuatu has chosen an alternative route through national legislation and institutional restructuring to integrate DRR and CCA.

There are two broad approaches followed by the Pacific Island countries regarding JNAPs and NAPs. One set of countries is working on formulating NAPs explicitly, with proposals and/or plans under way to access the GCF NAP formulation funding (e.g. Fiji, Tuvalu and Vanuatu). Another set of countries will characterize their JNAPs as their NAPs (Cook Islands, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau and Tonga). The second group of countries is planning to use the GCF NAP formulation funding to revise or update CCA components of their JNAPs to ensure full coverage of the features of NAPs.

One country, Samoa, is applying its national development strategy as the overarching plan for development planning, climate change, DRR, SDGs, etc., all in one, with no separate plans for the different issues. Implementation of activities is coordinated through the country's medium-term expenditure framework.The Cook Islands launched its second plan, JNAP2, in 2016, covering the period 2016-2020. This JNAP2 has nine sectoral strategies to ensure a safe, resilient and sustainable future. It aims at strengthening climate and disaster resilience to protect lives, livelihoods, economic, infrastructural, cultural and environmental assets in the Cook Islands in a collaborative, sectoral approach. The Paris Agreement and Sendai Framework are mentioned in the foreword, and there is a mapping of how both have informed JNAP.

The Kiribati Joint Implementation Plan (KJIP) is being updated to complement the National Disaster Risk Management Plan and the National Framework for Climate Change and Climate Change Adaptation. Among other things, the KJIP revision responds to the gender equality policy imperative set out in the Paris Agreement.

The Marshall Islands is updating its JNAP 2014-2018. It has set the adoption of SDGs, the Paris Agreement (together with NDCs and NAPs) and the Sendai Framework as the national policy context and guiding principles for updating its JNAP. The country plans to align its National Framework for Resilience Reform with its NAP to ensure appropriate relevance to funding.

Vanuatu has created integration of CCA and DRR institutions and policy development processes. The National Advisory Board on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction is jointly directed by the Vanuatu Meteorological and Geohazards Department and NDMO, and operates as Vanuatu's principle policy, knowledge and coordination hub for all matters concerning climate change and DRR. This was set up before the new law that formalizes integration.

13.6 Conclusions

13.6.1 Coordinated national policymaking for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction

Coordination can be achieved most effectively at the national level during the production of strategies and plans in support of development. CCA and DRR are both sufficiently flexible concepts to enable countries to develop and implement plans and strategies based on national circumstances and needs.

How countries report and produce plans in response to different multilateral agreements is a different issue; at times, these requirements can militate against integration. The international context also includes coordination of support that comes under the different umbrellas based on the special requirements of each source.

13.6.2 Coordinated national technical assessments and solutions for the full spectrum of risk

Risk assessments for climate change and disasters are often carried out by different teams, and are supported and guided by different agreements and bodies internationally. It must be recognized that although disaster and climate risk have significant overlap, there are also substantial aspects in which they do not coincide, and this is an important challenge for integrated risk governance at national and local levels. However, in the realm of hydrometeorological risk, for example, there is also a continuum of applicable tools from adaptation/risk reduction, planned or contingent, to managing extremes and disaster losses. A country could choose to coordinate these aspects of CCA/DRR assessments, provided the assessments cover the timescales relevant to each type of risk, from the present through to the medium and long terms.

However, as set out in Part I of this GAR, in fully integrated approaches under the Sendai Framework, there is also a need to include risk from non-climate-related natural hazards (especially seismic/tsunami, volcanic, fire and biological hazards), complex mixed hazards triggered or created by human activity (environmental risks, nuclear/radiological and chemical/industrial hazards), as well as the cascading or systemic risks that arise from these hazards and climate change risk, beyond the immediate effects of particular hazards or phenomena.

13.6.3 Integrated and coordinated activities - minimizing complexity and avoiding duplication

Many organizations have prepared supplementary materials to NAP technical guidelines, to offer advice on how to promote synergy with other frameworks. A supplement that covers DRR issues is under development by UNISDR and UNFCCC in close collaboration with the Least Developed Countries Expert Group on Adaptation, and will show how countries can better coordinate their efforts at the national level to address climate DRR and CCA through NAPs.

There are other global frameworks and multilateral agreements that also have actions which address CCA and DRR. For example, UN-Habitat's NUA, and regional frameworks such as Africa 2063, have areas of work that can be better integrated at the national level. A broader integrating framework can be applied, such as the NAP-SDG iFrame being developed by the UNFCCC Least Developed Countries Expert Group to support formulation and implementation of adaptation plans.

Any global attempt to create synergies can be successful only if coordination at regional, national and local levels is ensured by a strong lead institution with a coordination mandate. As DRR and CCA are issues that affect many sectors, isolated action is rarely successful, and real coherence can take place only if silos are broken at the level where implementation occurs.

13.6.4 Integration of disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation into financial and budgetary instruments and frameworks

Many of the country cases cited illustrate the importance of capacity and resources for implementation. While a strong governance mechanism and accessible risk information play a crucial role in implementation, risk reduction remains aspirational unless it is translated into a budgetary process. Instead of perpetuating institutional competition for separate resource streams, financial instruments need to be made available that consider the nexus between DRR and CCA and provide comprehensive financial resources. Financing mechanisms still need to be adjusted to the new paradigm.

Overall, the approach of integrating DRR into CCA plans seems to be most successful where hydrometeorological disaster risks are highest and the impact of climate change is felt most. It may not be the right fit for all countries, but it has a strong potential for accelerating implementation when there is political will.