|

ECLAC:

An Assessment of the Drought that Hit

Central America in 2001

The United Nations

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and the

Central American Commission on Environment and Development (CCAD) carried

out an assessment of the drought that hit the Isthmus in 2001, as requested

by the Central American authorities. The following is a summary of this

assessment, based on the figures compiled during a field trip and their

analysis based on an internationally accepted assessment methodology.1

An estimate is produced of the damage and losses caused by the drought

as well as those sectors and geographical areas that were most affected.

Finally, a proposal for future action is presented.

Between

May and August 2001, an abnormal hydrometeorological phenomenon hit Central

America, causing precipitation levels to drop well below historic averages

and severely affecting both the population as a whole and the production

and provision of sometimes vital goods and services. Between

May and August 2001, an abnormal hydrometeorological phenomenon hit Central

America, causing precipitation levels to drop well below historic averages

and severely affecting both the population as a whole and the production

and provision of sometimes vital goods and services.

Normally, the trade winds in the area begin to fall off around April,

making it possible for the winds from the Pacific to bring in increased

humidity and precipitation. In 2001, this did not happen. The anomaly

was linked to planet-wide atmospheric events that were, in spite of initial

fears, unrelated to the El Niño phenomenon.

Growing vulnerability

The drought affected

the Central American population in different ways and to varying degrees.

- Those who suffered

the most, lost their very sustenance: subsistence farmers who required

food assistance, as well as commercial farmers who lost their source

of income.

- The second most

severely affected group comprised those whose access to basic services

such as drinking water was curtailed or entirely interrupted, not only

causing them considerable inconvenience but, far more importantly, increasing

the threat of falling prey to communicable diseases.

- In third place

were those—essentially, close to the entire population of the subregion—who

were forced to pay higher electric bills as a result of the need to

supplement insufficient hydroelectric power with petroleum-based electric

generation.

The total number of

people affected in one way or another by the drought was estimated at

23.6 million, or 70% of the inhabitants of the subregion.

The largest impact

was on agriculture, as anyone could have foreseen given the ominous links

between drought, desertification, soil erosion, and lower crop outputs.

Since agriculture tends to provide employment for the most vulnerable

sectors of society—those with the lowest levels of education, income,

and access to other vital services—it was precisely those who could

least afford it who were the hardest hit.

The Damage

The Great Central

American Drought of 2001, as it will no doubt be remembered, compounded

two pre-existing situations, magnifying their impact and that of the drought

itself. One was the economic crisis caused by the international drop in

coffee prices; the other, the increased vulnerability as a result of a

succession of adverse climate phenomena over the previous five years.

Total losses in the subregion were estimated at US$189 million: 125.5

million (or 66%) in agricultural and industrial losses, 50.1 million (26.5%)

in higher costs for all productive sectors as well as lost revenue by

the water and electricity utilities. The remaining 7%—13.4 million—accounts

for the costs of responding to the emergency.

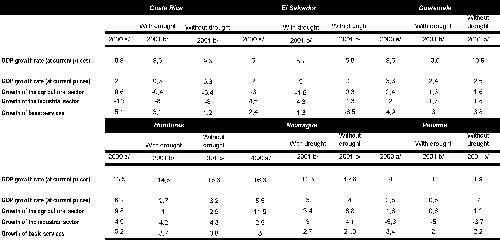

Tables 1. and 2. illustrate

the economic impact on each of the countries in the subregion.

Table

1. – Variation in the GDP as a result of the drought in Central America

|

Costa

Rica

|

El

Salvador

|

Guatemala

|

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

| GDP

growth rate (at current prices) |

8,9

|

9,5

|

9,5

|

6

|

5,7

|

5,8

|

9,5

|

10,8

|

10,9

|

| GDP

growth rate (at current prices) |

2,2

|

0,3

|

0,3

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

3,3

|

2,4

|

2,5

|

| Growth

of the agricultural sector |

0,6

|

-0,4

|

-0,4

|

-3

|

-1,6

|

0,3

|

2,4

|

1,3

|

1,6

|

| Growth

of the industrial sector |

-4,3

|

-8

|

-8

|

4,5

|

4,3

|

4,3

|

2

|

1,7

|

1,8

|

| Growth

of basic services |

5,1

|

3,1

|

1,2

|

2,4

|

1,3

|

-6,5

|

4,9

|

3

|

3,8

|

| |

Honduras

|

Nicaragua

|

Panama

|

| |

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

| |

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

| GDP

growth rate (at current prices) |

13,5

|

14,8

|

15,3

|

16,3

|

11,5

|

12,6

|

4

|

1

|

1,9

|

| GDP

growth rate (at current prices) |

6,2

|

2,7

|

3,2

|

5,5

|

3

|

4

|

2,5

|

0,5

|

2

|

| Growth

of the agricultural sector |

9,8

|

1

|

2,9

|

11,5

|

3,4

|

6,8

|

1,6

|

0,6

|

1,2

|

| Growth

of the industrial sector |

4,9

|

4,2

|

4,3

|

2,9

|

3

|

4,1

|

-5,3

|

-5

|

-3,7

|

| Growth

of basic services |

5,2

|

3,7

|

3,8

|

3

|

2,7

|

21,3

|

3,4

|

2

|

2,2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: ECLAC, based

on official figures.

a/ – Preliminary figures

b/ – Estimated figures

For the subregion as a whole, the implications on GDP and the external

sector can be appreciated in Table 2.

| |

CACM

|

Panama

|

Central

American Isthmus

|

| |

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

|

With

drought

|

Without

drought

|

| (All

figures in US$ millions ) |

2000

a/

|

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

2000

a/

|

2001

b/

|

2001

b/

|

| GDP

at current prices |

56.577

|

59.939

|

60.016

|

10.190

|

10.119

|

10.417

|

66.767

|

70.058

|

70.433

|

| Agricultural

sector – value added |

9.908

|

10.422

|

10.521

|

673

|

685

|

688

|

10.581

|

11.107

|

11.209

|

| Industrial

sector – value added |

13.560

|

14.238

|

14.252

|

759

|

779

|

776

|

14.319

|

15.017

|

15.028

|

| Basic

services – value added (Electricity, gas and water) |

16.917

|

18.894

|

18.902

|

1.949

|

1.985

|

1.992

|

18.866

|

20.879

|

20.894

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In short, when the

losses are viewed in the context of the economy of each country and the

subregion as a whole, they do not appear to be high. One might even assert

that, in normal vulnerability conditions, the subregion would have been

able to absorb these losses without too much difficulty. This can be seen

in Table 3.

Table

3.

Comparison of total losses caused by the drought,

with some macroeconomic variables

|

Country

|

Losses

(millions of dollars)

|

Losses

in comparison with 2000 export, %

|

Losses

in comparison with GDP 2000, %

|

| Costa

Rica |

8,8

|

0,2

|

0,06

|

| El

Salvador |

31,4

|

1,1

|

0,24

|

| Guatemala |

22,4

|

0,7

|

0,12

|

| Honduras |

51,5

|

2,5

|

0,91

|

| Nicaragua |

48,7

|

6,7

|

2,15

|

| Panama |

26,3

|

0,5

|

0,26

|

| Total

or Average |

189

|

0,6

|

0,3

|

|

|

|

|

Source: ECLAC

(2001), Balance preliminary de las economías de América

Latina y el Caribe, Santiago de Chile, December

Strategic Framework

for Drought Mitigation and Prevention

The effects of the

2001 drought cannot be understood systemically—holistically, as some

might say—without taking into account the feedback loops linking

negative environmental and socio-economic developments in the subregion,

and their impact on vulnerability. (See Flow Chart 1.) Vulnerability leads

to disasters, but disasters also increase vulnerability—and the Central

American Isthmus has suffered from a highly unfortunate streak of disasters

in recent years, including El Niño, Hurricane Mitch, and other

storms, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. From this point of view,

drought is the result of the interactions between climatic variations

and human activities.

A strategic framework

for drought mitigation and prevention is clearly needed to help Central

America respond to future extreme natural events and reduce their socio-economic

and environmental impact. This calls for a SWOT approach.2 What are the

strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats facing the subregion

in this area?

Such a strategic framework

must be cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary if it is going to deal effectively

with the full complexity of the phenomenon. A purely environmental, say,

or socioeconomic approach would hardly meet current needs—much less

an approach that focused entirely on responding to unfolding events. The

framework should be comprehensive and serve as a guide for the further

development of sectoral strategies—rather, “sub-strategies”—by

specialized institutions. Even this, however, will not be enough unless

civil society is vigorously encouraged to participate in the effort.

From Analysis to

Action

The ECLAC/CCAD Assessment

proposes a series of actions that might prove useful for decision-makers,

both in the technical and policy fields. In fact, the study stresses the

advisability of building on the foundations of previous expressions of

political will by subregional leaders who agreed to promote a development

model that is socially, economically and environmentally sustainable.

The frame of reference,

in this case, would be the Central American Alliance for Sustainable Development

(ALIDES), established in 1994.Any mitigation and prevention strategy must

also be linked to the various international and regional initiatives aimed

at vulnerability reduction, such as the United Nations Convention on Climate

Change and Desertification.3

Other efforts include the Strategic Framework for Vulnerability and Disaster

Reduction agreed during the 1999 Central American Presidential Summit,4

the Central American Five-Year Plan for Vulnerability and Disaster Impact

Reduction spearheaded by the Center for Natural Disaster Prevention in

Central America and Panama (CEPREDENAC), and the environmental commitments

by subregional leaders such as the Environmental Plan for the Central

American Region (PARCA).

For more information

please contact:

Ricardo Zapata

United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean

(ECLAC), Mexico

rzapata@un.org.mx

- This methodology

can be reviewed at ECLAC’s Mexican Website (http://cepal.org.mx/) and

the following World Bank Web site:http://www.proventionconsortium.org/toolkit.htm.

While the methodology is under constant review and improvement —an updated

version will be published this year —it is considered effective in providing

a prompt, comprehensive and impartial view of the socio-economic and

environmental consequences of any given disaster. It employs internationally

recognized criteria and can help countries perfect their own more detailed

assessments as well as formulate reconstruction strategies and disaster

prevention, mitigation and reduction policies.

- Strengths, Weaknesses,

Opportunities and Threats. Also known as SWOC (Strengths, Weaknesses,

Opportunities and Challenges—or Constraints).

- The Sixth Regional

Meeting on the implementation of the United Nations Convention to Combat

Desertification (UNCCD) was held in San Salvador on 16-19 October 2000.

An assessment was then presented of the social, economic and environmental

impact of desertification and drought in Central America. This meeting

was not the only one at the international and regional level to underscore

the need to take advantage of existing synergies between the Desertification,

Climate Change and Biodiversity Conventions in order to sharpen the

focus of current efforts and available resources.

- Presidents of

Central America (1999), Guatemala II Declaration, 19 October.

|